Tutorial 4: Critique

Critique is the practice of examining something carefully to understand it and learn, often in a “discussion” format. Critique is a key tool in learning about Vis, and in improving design (for Vis, and in general). It is also a generally useful skill that can be learned with practice.

This tutorial will give you a quick guide on how to do critique with the goal of helping you get started at improving your critique practice, or at least to appreciate why the examples in Critiques are the way they are. The simple “rules and formulas” here are good for beginners (including me) to get started. Maybe with practice, I won’t need them - but I think that experienced designers have internalized the lessons.

Critique is really useful for Vis. In the context of this site, I will use critique to analyze examples in order to try to distill their lessons, often to reinforce more general principles. In the practice of doing design, critique is often a way of understanding a prototype so that we can generate ideas on how we might iterate. Re-Design (see Re-Design below) often involves critique (at least implicitly), but not all critique involves re-design.

Critique is really useful beyond Vis. This is why I emphasize it in my class.

Designers and artists don’t own critique. Critique is for anyone who wants to improve anything that they are building or doing. Critique isn’t a ‘design’ skill, it’s a life skill. Discussing Design, p. xi

What I’ve learned (see Historical Note) is that critique is a skill that you can get better at with practice. The Critiques are practice for me, as well a chance to look at some designs and learn from them. If you’re trying to become better at Vis, I recommend trying to become better at critique.

Getting Started

I emphasize that critique (examining and discussing something to learn from it) is different than criticize (identify/describe the faults in something).

Central to critique is that there is some thing that you are examining to discuss. In our case, it will usually be a visualization.

Critique is usually described as a conversation where the designer is present (to help understand the design to get ideas for iteration). My observation: the same things that make critique work well as a conversation with the designer can also make it work well when the designer isn’t there, and the goal is more about learning (to draw conclusions from a specific example).

If you don’t do critique carefully, things can go wrong: you can (1) upset the designer and/or (2) fail to have a productive conversation. Critiquing in a way that is kind to the designer prevents problem #1, but seems to also prevent problem #2. Two recommendations: (1) pretend that the designer is there (even if they aren’t), and (2) critique the work, not the designer.

In performing critique, I recommend setting a few ground rules (these are paraphrased from Irene, a former student in my class):

- Know the purpose of the work

- Say something good

- Be specific about problems

- Don’t dictate

- It’s about the work, not the person

Which I alter/re-order into a list of “advice”:

- Critique as if the person is there (Critique the work, not the person)

- Understand/Examine first (Understand context and the object before reacting)

- Connect to intents (if you were trying to X then Y)

- Consider choices (what choice was made? how could the decision have been informed? (principles!))

- Do not prescribe

The Stylized Formula

To make critique easier, I recommend starting with stating critique using a stylized formula. Everything you “say” should be in this stylized form. Once you get practice doing this form, you may learn to critique well without it - but the form is a nice set of “training wheels”.

The stylized form comes from the Discussing Design book (first chapter preview). If you follow this stylized approach, you won’t commit the worst mistakes, and will probably be steered towards effective critique:

- Be clear about the objective.

- Be specific about the aspect of the design.

- Describe why/how the aspect works (or doesn’t) for the objective, with a principle.

This is very stylized, but it really does help us novice critiquers (judging from my classes):

If objective then decision could be informed by principle.

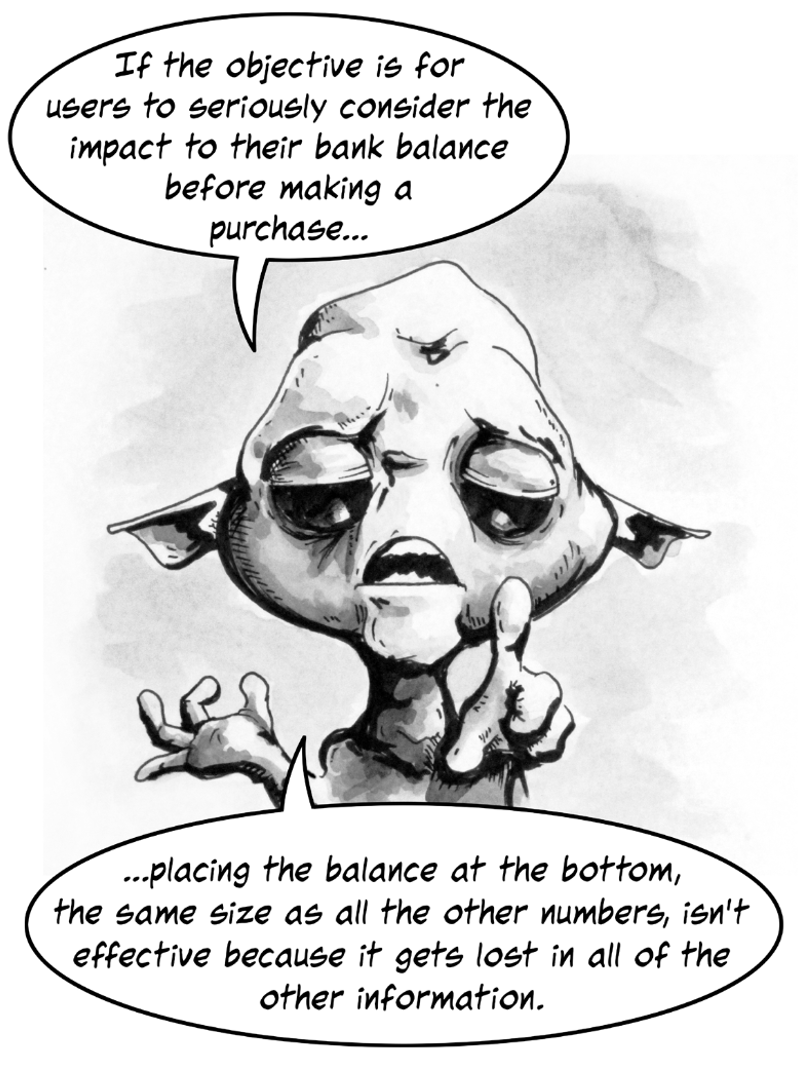

The book teaches this with great cartoons, here is an example:

Stylized form of critique from the book Discussing Design. From the book Discussing Design, used without permission.

Let me try that with a critique of what you’re reading (critique can be applied to anything - not just visualizations).

If the objective of this page is to help the reader understand how to apply critique practice, an abstract explanation may make it hard to connect the concepts to practice. Consider using an actual example to make things more concrete.

Notice how I stated a goal, a problem (relatively specific), and then a principle that could be used.

An initial example…

I wanted an initial example to show what can go wrong in a critique. This is easiest if it’s something bad (so it’s easy to find things to talk about). And since the critique errors often are painful for the designer/creator, I wanted someone easy to pick on… So I asked Microsoft Co-Pilot (ChatGPT/Dall-E) to make something…

An intentionally bad chart made by CoPilot.

Yuck. That is so terrible that I am not sure I can critique it.

Notice how unhelpful that last line was. You aren’t going to learn much from me saying it. In class I say “try to say something more constructive than yuck.”

Let me try again…

The designer doesn’t understand visualization. If they took a Vis class they should have learned that those extra things are bad.

In some ways, this is worse: if the designer was a person, they would probably be upset - it doesn’t help us to accuse them of what they don’t know. I could imagine ChatGPT responding (if it wasn’t so polite) - Actually, I have built all the materials from your classes into my model, and I intentionally added those extra things because they better responded to the prompt.

Pure prescription wouldn’t help either:

Get rid of the flying donuts.

Why? Maybe the designer tried other things, and had a good reason for this.

Let’s try the stylized form…

If the goal is to create an image we can use for learning about visualization critique, a chart with too many things going on might be too distracting. Getting rid of extra objects can simplify the design and make it easier to identify specific features.

Notice how this is non-antagonistic. We give the designer an out “I wasn’t trying to create an image for learning about visualization critique, I was trying to obey the prompt.” The critique identifies the aspect and why it might be a problem. It tries to evoke the principle (too many things are distracting, simplicity makes it easier to identify things).

1. Know the Purpose - establish the goals and context

Understanding the context of the object - what was it intended for - is important because the design really needs to be examined in terms of how well it achieves its goals.

For a Visualization, this usually means the task or message that the visualization is trying to convey, which often requires examining what the visualization is for. In doing visualization critiques, we often see the visualization out of the context it is meant to appear. For example, we see a figure from an article (newspaper or academic article) without the context of the story it is trying to support. We should establish enough of the “story” so that we can understand the visualization and its intended message/usage.

Sometimes, you might ignore the context. “I (as critic) don’t care what this visualization is about, I want to use this as an opportunity to explore this element.” But even in these cases, it is useful to have context/purpose as it helps avoiding other problems (like blaming the designer for something that weren’t trying to do).

2. Say Something Good

The point here is to show understanding of the object. It’s less about saying something nice to be kind to the designer (to warm them up before knocking them down), but rather to show that you have taken the effort to appreciate what has been done (for better or worse).

I change this to “understand/examine first”. This is related: if you don’t try to understand and examine first, you might respond with the first detail (often negative) that catches your attention. These “initial yuck responses” are rarely constructive. (Although, they are useful - if you have an “initial yuck response” be aware of it, and then come back to figure out why).

3. Be Specific

I generalize this (Irene said “be specific about problems”).

Vague and general statements are less easy to learn from or connect to principles, guidance, or potential changes.

4. Don’t Dictate

The goal is to inform - to learn from the example. Not (just) to say what you think should have been done instead.

So often, a “you should X” could be responded to as “yeah, I tried that and here are a bunch of other problems that come up.” Or “why did you pick that.”

Example to consider: If the goal is to draw attention to those key words, they should stand out from the rest of the text.

- I would make them red. tried that, and my client hates red text

- Consider ways to make them contrast the other plain black text. For example, red would be very different. I can’t do red, but maybe another non-black color would provide enough contrast, especially if I find other ways to create contrast such as using italics.

5. It’s about the work, not the person

Keep focused on what you are critiquing. Good designers make bad things sometimes (maybe they were rushed, or exploring something risky, or having a bad day).

If there is a problem, don’t assume that the creator doesn’t know better. If there is something good, don’t assume that the creator has the same reasoning that you do.

Critique is different than assessment: if your goal is to judge the person/process (to give them/it a grade), then you are doing something different from critique.

Do I have to use the stylized form?

The me the stylized form is: *If objective then decision could be informed by principle.

Do you have to use this? No - I suspect expert critiquers (experienced designers) don’t critique in this stylized way. But in my class, I force us all to start with the stylized form

Notice how the stylized form steers away from the worst problems.

- It gets away from offending the creator as it gives them an out. “If the goal was X” let’s the creator say “that wasn’t my goal” or even “that wasn’t my priority”.

- The focus on a decision not only makes this about a specific aspect (giving the critique focus) but also steers towards something you can do something about.

- Connecting the objective and decision keeps things on track - doing it with a principle helps provide rationale (so it is more than opinion) and helps bring in general principles so that learning can generalize beyond the examples. It also helps generate ideas (by suggesting options, rather than a specific choice).

Besides Critique

The Discussing Design book emphasizes that critique is only one of many forms of dialog. This was good food for thought for me. Here is my list, adapted from theirs:

- Critique is not opinion. You are entitled to your opinion and personal taste. But you should own it as your opinion. It’s OK for you to say “I dislike purple text” or even “If your goal is to make things that everyone likes, consider that there are some people like me who dislike purple.” I am allowed to dislike purple - but I should “own” that opinion.

- Critique is not assessment. The goal of critique is not an absolute judgment of good or bad, it to gain understanding. Critique is about the object being critiqued (although, the process that made it might be relevant). Critique might be useful in assessment. For example, critique might point out how a design could be better informed by principles. Assessment could say “the student who made it was supposed to be considering those principles, so I can infer something about their understanding of the principles from the design.”

- Critique is not direction. The goal is to understand the design, which might suggest alternatives. It shouldn’t (just) be trying to prescribe an alternative. It’s OK to make suggestions - but use them as a way to connect with principles. The designer may have already considered the alternatives.

- Critique is not the only kind of feedback. In fact, critique can be used for things other than feedback.

Re-Design and Critique

One place where critique is powerful is in understanding a design to see what different choices might be made. These different choices can be called “re-design” or iteration.

Critique is a really powerful tool in doing re-design (or design iteration), because it helps understand the current design and how it might be improved (or the good things that should be preserved).

The stylized form can be helpful: it can point to specific choices that could be made differently, leading to different designs that can be critiqued (possibly in a comparitive crtitique where it is examined with alternatives to understand how to choose).

I recommend this posting (from two visualization experts) as a great discussion of redesign with good examples:

- Design and Redesign (Medium posting) by Fernanda Viegas and Martin Wattenberg

Historical Note

When I started teaching Vis, I appreciated critique as a key tool. I saw it as something that designers did well as part of their (iterative) process. I saw it as a big element of learning visualization. I observed in class that students who had formal design training (e.g., an undergraduate degree in Industrial Design or Architecture) were better at it.

In my 2013 class I had a breakthrough: one of those students who was good at it (she had an undergraduate degree in Industrial Design) volunteered to do a project: design a single class to introduce Vis students (mostly Computer Scientists and Engineers) to critique. Her conjecture… a single class would help students get started to becoming better at critique. Ultimately, it’s a skill that takes practice… but a little bit of instruction, and a little bit of intentional practice would set students on the path of becoming good at critique.

Her crash course in critique was a smashing success. It consisted of a brief “lecture” followed by practice, where students did critiques - and then did critique of others’ critique. I thought it was fabulous - I learned a ton. And other students appreciated it too.

Over the years, I evolved that exercise. The biggest difference: I now do it the first or second week of class so students have it as a tool for their learning. I’ve tuned the lecture part a bit and freshened the examples. But, the activity is pretty much the same. It forms the basis for this document. (If you are a student in my class, you will do this).

A second improvement came when I discovered the book “discussing design”. This is an entire book dedicated to teaching critique. The intro chapter (that the authors/publisher generously make available for free) is a fabulous tutorial on critique. The chapter is required reading in my class. The book gave me is a structured “formula” for doing critique (Objective, Aspect, Inform/Principle).

Part of the Vis Snacks project is to force me to do more critique (in written form) in order to improve my critique practice. I invite you to critique along with me to improve yours.