Tutorial 1: What Is Visualization and How do We Do It?

This gives you a sense of my thoughts on what Visualization is, and how we best go about creating them. By defining visualization in a clear and operational manner, we can better organize our thinking about what it means to do visualization well (which is our goal), how we should go about doing it, and what we need to learn to do it.

Warning: this document is a little skewed towards the “vis is more than just implementation” message, because the original purpose of this document was to explain to CS students why my class doesn’t focus on implementation.

The Key Points

- A visualization is a picture that helps someone do something.

- Implementation is not the central concern.

- A Good Visualization is one that is effective at helping the viewer achieve their task. A good visualization is a picture that makes it easy for the viewer to see the thing they need to see.

- Good visualizations usually need to be designed (created by intentional choice).

- Good visualizations don’t have to be fancy.

- Don’t bother solving the wrong problem well.

- There is a 4 step process to creating a visualization: Task, Data, Design, Details.

- Abstraction is a key tool in thinking about tasks and data.

- There are 4 components to visualization designs: transformation, layout, encoding, and interaction.

Learning Goals: This document is designed to help introduce you to the basic concepts and ideas of the class. It provides a basic framing for the topic, and a brief skim over some of the initial topics we will be exploring more deeply in the coming weeks.

- Understand what we mean by visualization.

- Appreciate at a high level what we are trying to achieve with good visualizations.

- Have a sense of what the visualization design process will be.

- Get a look ahead at what we will be doing in class.

- Have an intellectual framework for things in class.

About this document

This document is basically a written form of the introductory lecture I like to give in class.

It has a long history, and it has evolved (which is why it keeps getting longer - please bear with me, this is important stuff).

The original purpose of this document was to give a sense of the philosophy behind the class, which is really my philosophy of visualization. It explains why my ideas on visualization lead to the specific class design. A lot of the “philosophy of the class” has been moved to class documents (2024 version 2022 version - others are similar). I point out this history, because it may explain the unusual form of the document. It also explains the over-emphasis on de-emphasizing implementation (I want to warn students this isn’t the typical CS programming class).

The purpose (as an initial class reading - or as an introduction to the Vis Snacks website) is to provide an “intellectual framework” that we will build the class around. Whether or not you agree with my philosophy of visualization, it will provide us a scaffold to organize the things we need to learn. Hopefully you will see how we can start from defining visualization and have this lead to the main topics from class.

Note: there is an alternate purpose of providing a brief dose of visualization ideas for people who do not take the class.

You might think of this as a summary of the most important points of the whole semester condensed into a single blog posting.

This is adapted from my usual first lecture in class - except that it doesn’t have as many fun example pictures. However, since lots of people don’t get to see that lecture, this tries to get to the main point. And even if you do get to see the lecture, it’s a reminder of the key points.

What is Visualization?

I like to start with defining Visualization. Not because it’s important to be able to identify what is and isn’t visualization, but because I think it’s good food for thought and helps organize our approach.

My definition is:

Visualization: a picture(1) that helps someone(2) do something(3).

All three of these parts (1) picture, (2) person, and (3) task are important and deserve some discussion.

Pictures and Implementations

First, there’s the picture part. Basically, a visualization is something that you look at (it is “visual”). You might argue that we should relax the “look at” and bring other senses to bear (e.g., auralization to communicate data via sounds). However, while there are similarities between vision and other senses, there are enough differences that I think its best to focus on visual things (things we see) for this discussion (and the class).

I am using the word picture (since that’s usually what it is) as place holder, but it might be a moving picture (like an animation), or it might not be a picture in a traditional sense. For example:

One way to implement a bar chart. from dataphys.org

A physical object that you look at can be a visualization (like the blocks of snow or the lego model in a picture below). Or a visualization could be an animation, or a sketch on the back of a napkin, or some interactive thing on a screen.

Implementations can take many forms. I’m not going to suggest you make snow sculptures (like the pictures above), but maybe prototyping with Legos (picture below) is a way to try things out. Your choice of implementation strategy is almost always dictated by practical issues (where you need to show your visualization, what tools are available, …). The appropriate tools change quickly. The principles of choosing what to make with them do not.

A side effect of this is that we are not going to focus on programming. In fact, later in this document, I’ll argue that the goal should be to avoid programming. If you can get by with existing tools, you should.

Tasks and Good Visualizations

The important part of the definition is that it helps someone do something. What makes a picture a visualization is a sense of purpose: it’s going to be used for something.

Central to my definition of visualization is that it focuses on this sense of “task” - the picture is meant to do something, so we should think about what it is trying to do to make sure it really can help someone do the thing it’s meant to do.

The definition doesn’t necessary say that the visualization succeeds at helping someone do something. We can certainly have bad visualizations that don’t help. Effective visualizations (good visualizations) are pictures that really do help their intended audience achieve the task.

Making visualizations isn’t hard. Making good visualizations is hard.

Aside: In Munzner’s book, she defines visualization as being “designed to be effective.” In my mind, she is defining good visualizations - bad visualizations might not be effective, or might not be designed.

My goal (in this page/site/class) is to teach you how to design/create good visualizations. With the emphasis on the “good” part - making bad visualizations doesn’t have to be hard, and is probably not worth the effort.

Tasks as the Key

Let’s try the lesson with an example…

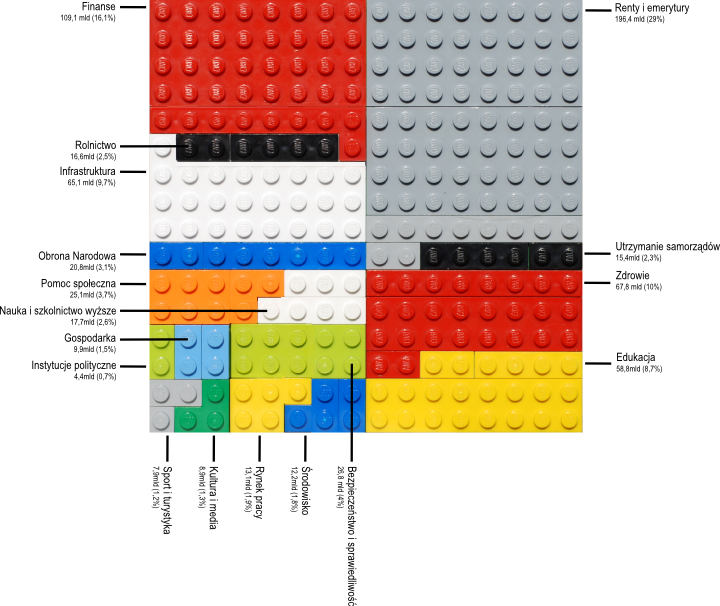

A Tree Map made of Lego from dataphys.org

I like this example because it shows that you can be creative with implementations. The visualization is a TreeMap - it is a fairly common design. The fact that it was made with Legos (rather than, say, Excel or JavaScript) is less important to how it communicates than the fact that it is a TreeMap, which enables the viewer to do certain things. For example, you can pretty quickly tell that large gray area in the upper right is a bit more than a quarter of the whole. There are other things this design is less good for. The fact that it is Legos is less important (although, it is cute).

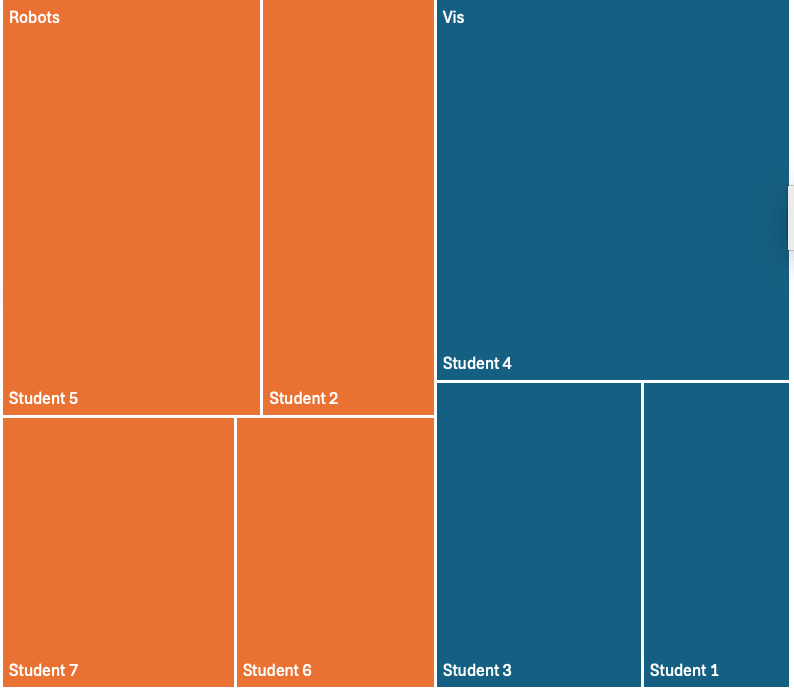

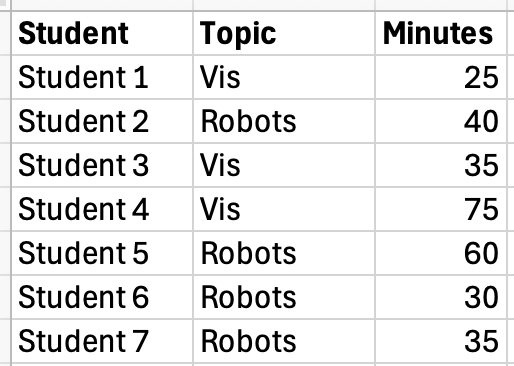

Let me make a simpler example in English with some small fake data. I met with 7 students, some students work on robots, and some work on Vis. I put the times into Excel and made a treemap:

A Tree Map made from Fake Data

Again, notice there are things you can tell pretty quickly. I spend a about half my time on each topic, although I spend a bit more on robots (orange) than vis (blue). You can tell I spent about a quarter of the time with Student 4 (upper right). Some things are less easy to see quickly, such as “which student did I spend the least amount of time with”. The fact that these “tasks” are easier or harder is the nature of the design: TreeMaps are generally good for showing part/whole relationships.

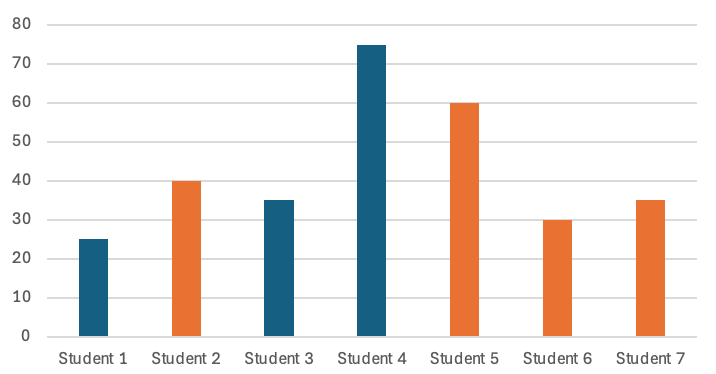

This point might be clearer with another chart of the same data:

A Chart made from Fake Data

This is a very familiar chart type. You can tell very quickly that Student 1 had the least amount of time, or that Student 6 got 30 minutes. In order to see “did I spend more time with orange or blue students” or “was blue about 50%” you would need to do some mental arithmetic.

Hopefully, I’ve convinced you that these two charts are good for different things. This is because of their design: one is designed for part/whole, the other for showing individual details. The design matters more than the implementation. Even if I made them in Legos, they would still serve the same tasks. The designs make some things easy to see (and other things less easy to see).

It is hard to say that one of these charts is better than the other. One is good for some things, the other is good for other things. If the purpose is to allow the viewer to quickly assess how much of the whole a group represents, then a TreeMap is great. If the purpose is to allow for getting specific values, then the TreeMap is not as good (for a variety of reasons we’ll learn in class). The lesson here is that task matters.

I’ll repeat this a lot: task matters. Don’t solve the wrong problem well.

How to think about Vis: Strategies and Names

To continue with the example, in the previous section I called the TreeMap by a standard name used for that design. And I made statements about what TreepMaps were (and were not) good for.

This suggests a strategy for learning Visualization: learn a long list of chart types, learn what they are good for, learn how to make each one well. I think this is a terrible way to learn visualization. Instead, I prefer to teach visualization by understanding the principles (such as the importance of task) rather than as a long list of chart types.

Notice that I did not name the other chart. I would have called it a “bar chart” or maybe even a “vertical bar chart”. But Excel uses the term “bar chart” for something else - it calls the thing above a “column chart.” Amazingly, it works the same no matter what you call it. We might not agree what to name it, but we probably can agree on what it is good for.

We can think of these charts not as their “types”, but rather in terms of the building blocks that make them up. An example of a useful kind of building block is encoding - how a data element is translated to visual elements. Whether you call it a “vertical bar chart” or a “column chart”, that chart encoded the values (in minutes) by the position of the top of the rectangle along the Y axis measured from X axis (a “common baseline”). For reasons we’ll learn about later, we prefer to say “position on common baseline” rather than “height of rectangle” or even “area of rectangle” - even though, in this case, all three of these are actually proportional to the data.

Some advantages to thinking in terms of encodings:

- We can understand how the encodings communicate, which help us reason about whether using a particular encoding is likely to be effective for a particular task.

- We can use these understandings for many different possible charts.

- We can mix and match encodings. (notice that in both charts, I encode “topic” with color)

Once we learn that position along a common axis encodings are good for reading precise values and seeing the largest / smallest, then I will know that many different visualizations based on this will be good for those tasks. Color is good for showing a small set of categories and can be added to many kinds of charts (combined with other encodings).

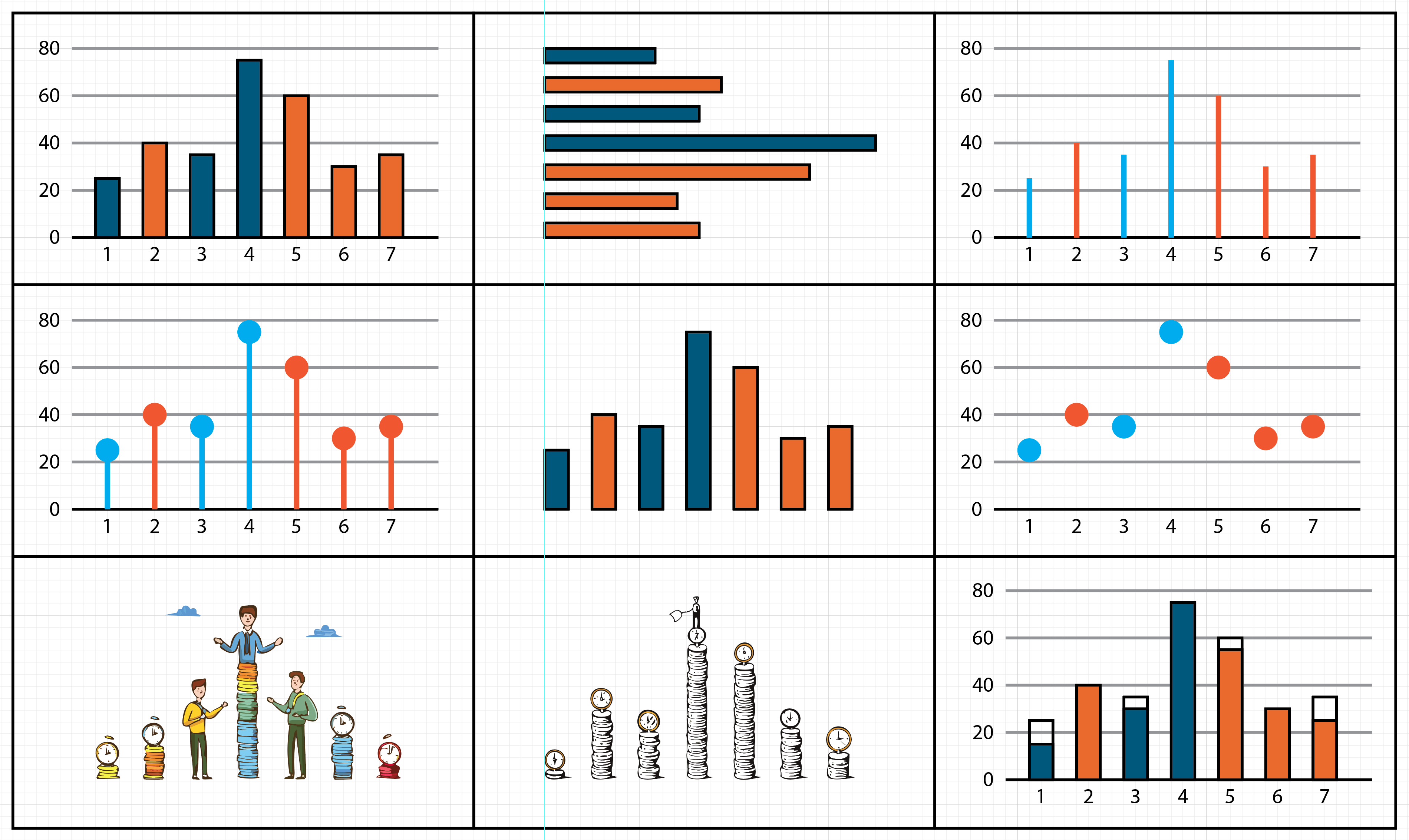

Here are 9 different visualizations of this same data with “position on common axis” encodings:

9 visualizations that use position-on-common-axis encodings to encode the same Fake Data. The left two on the bottom row were generated with AI fill in Adobe Illustrator and distorted the data. The amount of the distortion of the bottom center is shown by the bottom right visualization.

The key building block of the designs - position on common axis encodings - makes it possible for us to know what tasks they are all well suited for. For example, they are all good for quickly finding the biggest, or comparing two individuals. The differences in the visualizations do matter (e.g., the ones that don’t correctly encode the data are problematic, the big circles create some ambiguity in values, etc.). Details are important, but only if you get the basics right. And those details can also be driven by principles (like, be careful about distorting the data).

And, to add one more point about naming: here is another visualization of that same fake data:

A Chart made from (the same) Fake Data

Yes, in my mind a table is a visualization. They are very good for some tasks. See Tutorial 2: A Simple Example: 4 Design Moves on a Table for an example of how the ideas discussed below can be applied to a table.

But, the point… my “method” is to think in terms of building blocks and principles, not chart types. It doesn’t matter what we call things, it matters that we make choices that serve the viewer’s tasks.

How to make Visualizations: Design

Design (as a verb) is another term that is difficult to define, but worth discussing. Defining design is a whole philosophical debate – but the definition I am about to give is one I like, and will work with for the moment. The dictionary definition says something about planning how to make something. For the purposes of class / our discussion, I will define design:

Design (v): the act of making purposeful choices in the creation of something.

The idea is that what makes something design is that you actually think about the choices. You don’t just do any old thing - you actively choose. This is why I can distinguish between “bad design” (choices were made, but not well), and “not designed” (the choices weren’t thought about).

For this class or this website, the concept is that if you think about the choices you are making when creating a visualization, you will create better visualizations. But this holds true for almost anything you create. For example, if you are doing “Graphic Design” (for example, trying to make a nice looking and functional website or business card), the important thing is to consider the different choices that you are making.

What are good visualizations?

To make a good visualization, we need to decide what a good visualization is. And then we can consider a process to make them.

Defining “good” visualizations will be a major topic in this class. Evaluation considers how we decide if a visualization is good or not. At a high level, the definition of visualization provides an answer:

A good visualization is one that effectively serves its intended purpose (helping the audience do the thing the visualization was meant to help them do).

Exactly how to measure whether a visualization does what it needs to do is more challenging, and is a topic we’ll come back to.

Here’s a second way to think about good visualizations:

A good visualization is a picture that makes it easy for the viewer to see the thing they need to see (in order to do the thing the visualization was meant to help them do).

This simple definition is something we will keep coming back to. The reason that we like visualizations is that pictures can make some things easy to see. The human visual system (it’s more than just saying “our eyes”) is remarkably good at looking at something and extracting some things from a picture, very quickly, and without much effort. A well chosen picture (i.e., a well designed visualization) can make useful things easy to see.

This would be a great place for an example - but I am not putting it into the document. We’ll look at a lot of examples over the course of the semester. Looking at and learning from examples will be one of our key tools for learning!

So, if you want an easy way to assess a visualization, ask yourself “what does this picture let me see easily?”

Aside: there might be other goals. I am assuming we are creating a visualization to communicate. If we had another intent we might prefer visualizations with different qualities, for example if our goal was to show off our programming skill, we might prefer fancier visualizations even if they communicate poorly. Arguably, even in this case the ideas apply: a fancy visualization might let the viewer see that the developer is a good programmer, even if it doesn’t help the viewer learn anything about the data.

Bad Visualizations

Another way to think about wanting to make good visualizations is that we want to avoid bad ones. There are a few different types of “bad” visualizations - these are things we want to avoid.

The definition of bad visualization is tricky, because there are many ways for a visualization to be bad. A few to consider…

- A bad visualization might fail to make things easy to see.

- A bad visualizatiom might make the wrong things easy to see.

- A bad visualization might make it easy to see something that isn’t there.

Notice how this connects to task. There is something that the viewer should see (in order to achieve their task). Maybe the visualization does not make it easy to see this. Worse, it might distract you: it makes something else easy to see. And, there is the really bad case where the visualization is actively misleading: the thing that is easy to see is actually wrong.

In some cases, a visualization can actively mislead someone. More often visualizations just fail to make things easy to see.

Again, this would be a great place for examples, but I am not putting them into the document now.

It is tempting to list a bunch of rules that will help you avoid making a bad visualization. In most cases, you can figure out that the rule is trying to help you avoid making the wrong thing easy to see, or the right thing harder to see. But, rather than trying to learn a lot of specific rules of things to avoid (or to do), I think it’s better to try to understand the general principles of what makes things easy (or hard) to see. This is why the class will focus on principles.

Implications of the Definitions

- A core of this class will be understanding what makes for a good visualization, and what we can do to design them.

- Figuring out what good visualization to make (designing it) is important, we don’t want to waste our time implementing bad visualizations.

- Understanding the principles and process of visualization can help us figure out what visualizations will be good before we invest too much energy in making them.

- Generating ideas for visualization and making sure they are good (and will lead to good designs when they are fully implemented) is my preferred approach. Finding ways to “prototype” ideas so we can assess them before investing too much energy is important.

- Implementating the design once you have it is not a focus in this class. It is a detail. A sometimes challenging detail. And it is definitely a practical concern: a great design isn’t of much value if you can’t make it real.

Fancy and Custom Visualizations

Note that a good visualization doesn’t have to be fancy - it has to be effective / get the job done. In fact, using a standard design is often desirable: you don’t need to teach people how to use a new design, and you can probably find an existing implementation.

Here’s my favorite analogy. You go to the doctor’s office because you feel sick. The last thing you want to hear is “That’s a novel and interesting problem! We need to devise a novel treatment. Let’s write a grant proposal and hire some research assistants…” No, you want to hear “I’ve seen that before. No problem. Take two aspirin and see me in the morning.”

As visualization practitioners, our goal is to be able to look at a problem and make those kinds of prescriptions. Task identification and abstraction are key here. It’s how we can say “I’ve seen that before” and get to “take two scatterplots and see me in the morning.”

Most problems we encounter are similar to other common problems, and the answers have been well-tested over the years. We usually don’t need a fancy new design: an existing, standard chart type probably will do the trick. Using a standard design has a lot of advantages: we don’t need to invent it, we don’t have to test it, we can use existing implementations, we don’t need to train the viewers to interpret them, …

This might suggest that as a visualization expert, you need to learn many different kinds of charts and rules about when they are appropriate. However, another path is to understand the design of charts in terms of the basic building blocks, and the basic principles by which these building blocks are put together. This is the approach to how we design visualizations.

How to make a good visualization

The description above leads to a pretty simple recipe. Basically, there are three things to think about (that come from the definition):

- Why are you making this visualization? Who are you trying to help? What are you trying to help them do? I refer to the latter as the “task” - and it’s usually more important than the who part.

- What data are you trying to use to achieve this task?

- How are you going to use the data to help achieve the task?

I split question 3 into two parts. There’s a planning part, and a part where you make the plan more concrete by filling in the details. Which leads to the four step recipe.

- Task

- Data / Resources

- Design

- Details

In the ideal world, you start at the top, and work your way down through the list. The steps are iterative: at the end of each step (ideally) you do some evaluation (e.g., critique) and maybe go back to a previous step.

Sometimes the steps don’t happen in order. For example, you really want to use a particular tool, try out a new algorithm, or make things a particular color, so you go looking for something to make with these details.

Sometimes, the process seems to start with #2 (Data): one gets some data and needs to figure out what to do with it. But this is actually an initial task: find what is interesting in the data. Often there is an iterative cycle - as the designer understands the data more, they can refine the task.

In a little more detail…

- Task - understand what the purpose of the visualization. Who is it meant to help? What is it meant to help them do?

- Data - what resources are available to help achieve the task? The main thing is (usually) the data.

- Design - what is the strategy for mapping the data into something visual?

- Details - how will you make this strategy into a specific picture / system that produces pictures? What are the specific choices (e.g., colors, implementation, …)

Later in class, we’ll see that this parallels Tamara Munzner’s nested model for validation. (We’ll read about it in her book, but was a great paper first). I think in terms of visualization design, not just validation (but evaluation is so important to design that it might not matter), so I adjusted the layers a bit.

If all goes according to plan, you’ll understand these 4 steps in the first few weeks of class.

How do we think about tasks and data?

The better that you understand what the visualization is trying to achieve (what will it help the viewer do), the more likely you will come up with a good solution. In the end, everything serves the tasks.

Note the plural: you may have a set of tasks. Often, there isn’t just one at a time. There are a set of things that a set of someones may want to do for a set of reasons. And maybe your solution will address many of these.

I was going to say “it starts with the tasks,” but sometimes you start someplace else (like you have some data and say “I’d like to do something with it” – but even then, I would probably say you have a task: figure out what the right questions to ask are!). However, in those cases, it’s really important to remember that task is key: the sooner you get to “what is this thing going to do for someone,” the better off you are.

This is also not to say that you need to fully understand the task at the beginning. Sometimes, your understanding of the task is hazy, or changes as you learn more (from later stages).

Task is an informal, fuzzy notion. It doesn’t always get explicitly written down or defined. But the clearer you are about it, the better off everything else will be. You can’t succeed unless you have something to succeed at.

One other detail on task: there is a range of kinds of tasks. There are abstract tasks and concrete application tasks. This is actually a spectrum/continuum.

While task is the most central thing, it’s also hard to talk about. We lack good, rigorous ways to talk about it. For the longest time, it meant that it didn’t get discussed enough (in the literature, in my class, in my work, …). The fact that it is hard shouldn’t get in the way of us trying to get better at thinking about it. We particularly lack good ways to talk about different levels of task abstraction.

Where I start…

When I talk to a new (potential) domain collaborator, I always start with the question “tell me about your science.” I want to know the big picture (the why) – because without it, it’s hard to have context.

My first goal is to identify the problem that needs to be solved – it won’t help anyone if we solve the wrong problem. Don’t spend time solving the wrong problem well.

Usually people come thinking they want specific help – they want to start with the data, or worse, with the way they are looking at their data (can you make a better chart for me? not without understanding what you are trying to do, so I know what “better” means!) We will get to that, but I think its important to identify the task.

I’ll stress this: if you want to be a visualization scientist (or more generally, a data scientist or computer scientist), one of the best skills you can have is to be able to help people identify their problems. I think it’s hard for people to identify their problems. Part of this is that people get so caught up in the details, that they lose sight of the big picture. Or that they are so set in how they do things that they lose the ability to imagine alternatives.

And, as computer scientists (and/or mathematicians), we have a secret weapon: abstraction. This is something that we value/stress much more than other disciplines. For this task phase of visualization, abstraction is a key tool. If we can recognize the abstract task for which the real problem is an instance of, the path to solving it becomes much clearer.

At one level each situation is different. Everyone thinks their problem is unique and special. The challenge is to have ways to think about visualization (data understanding) problems in a way that lets us see how they are similar to other problems. We need to hide the details of the specific problem. This is where abstraction comes in.

How do we make a design?

A design is the plan for how you are going to turn the data into a “picture” that helps with the task. This is why it’s so important to understand task and data before trying to make a design.

One you know your task and your data, you can try to design a solution. I say “design” to explicitly separate the act of coming up with the idea and actually building it (implementation). Design is the act of making conscious choices to solve a problem.

In terms of the class, a big part of what we’ll do is focus on design. What are the choices you can make, and how can you make good choices.

There are four main categories of things that we consider in designing a visualization. You can think of these as the kinds of choices you can make, or the kinds of building blocks you can build a visualization out of.

- Data Transformations - we compute some derived thing about the data that will be useful in one of the other steps.

- Layout - we decide where things go. Technically, this is a position encoding (see encodings below), but position is such an important thing, it gets it’s own special category.

- Encodings - an encoding is how we choose to map a data variable to some “visual variable” (an attribute of what we see - like color). Position is a visual variable, but it’s special enough that it becomes its own category (see layout).

- Interaction - taking user input is another thing you can do in a visualization. Often, input can be thought of as mapping input actions to changes in the visualization.

Another way to think about this is as “re-design” rather than design. We start with some visualization (a design), pick one of its choices (one of the 4 kinds of building blocks), and change it. I like to think of these like moves in a turn-based game, at each step I pick one of these things to either add (or change, if I am doing redesign).

For a simple example of applying these four design elements in a redesign see Tutorial 2: A Simple Example: 4 Design Moves on a Table.

Almost everything we do in designing a visualization turns out to be making one of those 4 kinds of choices. Almost every visualization can be thought of in terms of these 4 building blocks.

I find this list to be a useful way to organize the larger list of more specific things you might do. Most things fit into one category or another. I won’t waste time arguing this is the best categorization – but it’s good enough to give you a sense of the kinds of things that you can think about.

We’ll learn how to choose these different components, and use them together. We will look at visualizations and try to understand them in terms of these four components. We’ll think about redesigning visualizations by changing the choices. We’ll try to develop a sense of how to map tasks and user goals onto these kinds of choices.

How do we make good choices for design?

Creating a visualization is about making those choices for a design so that the result is effective for the task… but how can you choose wisely?

Part of it is trial and error. Sorry. We learn by examples. Reflecting on examples that we make (prototyping), and examining examples of others carefully (critique).

But there are things we can use that can hopefully help us make better choices. Some examples (which are, of course, things we’ll study in class):

- Principles of Visualization - Over time, people in the field have gotten some ideas about what works and what doesn’t. Sometimes, this folklore is made up and may not be true. Other times, it comes from experience or has been proven by experiments.

- Principles of Perception - Understanding how people see (as in how the visual system works and how the brain interprets images) provides a lot of useful clues as to what designs will (and won’t) work.

- Principles of Visual Design - General ideas on how to make things that are “nice” visually and communicate effectively. These principles are the same if you’re designing a visualization, a web page, your resume, … - so they are good principles to learn!

- Examples - Looking at existing examples - both good and bad - can help us. Sometimes, we can gain intuitions so we can make new designs. Other times, standard solutions provide us with answers, or at least a starting point.

But what about implementation?

Actually realizing the design is the last part. Well, not really, since usually the process of making a visualization is iterative: once you make something, you learn from it, and refine some of your earlier work, and try again.

If you were thinking “this is a CS class, we should focus on implementation,” you will be disappointed. As I’ve said, this class is more about how to figure out what the right picture to make is (e.g. the design) than how to make it. It’s a waste of energy to spend time making the wrong picture.

In the ideal world, you can think about implementation last – it’s an afterthought. In practice, the constraints of having to implement things will probably influence the kinds of designs you will want to consider. A design becomes less attractive if it’s too hard to build. In practice, there’s often a tradeoff between the practical issues of implementation and having the best design.

Even within implementation, there is a spectrum of levels. I like to think of this as “fidelity of prototypes.” In a sense, you can think of a back-of-the-napkin sketch as an implementation of a design. Most likely an incomplete, non-final one, but an concrete instantiation. It might be a good enough implementation that you can evaluate your design and decide if you want to pursue the design further (and make a higher-fidelity prototype). If you’re lucky, a crude prototype might just solve the actual problem.

One thing I like to stress is the importance of prototyping to explore designs. It’s best to try out lots of ideas, and see if you can figure out their problems before investing a lot in implementing them. Good “Designers” (graphic designers, industrial designers, …) usually like to explore an entire space of designs – by using very crude “implementations” (e.g. sketches).

Data analysis tools – things like Excel (yes, Excel will turn out to be my favorite visualization tools) or Tableau or … – often let you prototype lots of different things with your data. This “playing” with data – re-ordering it, making various kinds of pictures with it, looking at it all kinds of different ways – is actually a form of rapid prototyping. You can explore a lot of designs easily – often to decide that they don’t solve your problem – but sometimes to see that some of the simple elements actually can help. This “playing with data” (if you can do it) is a lot like sketching a lot of visual designs.

Having a good toolbox so that you can implement your designs is useful. If you don’t have one, you will be limited in what designs you can explore, and won’t be able to choose designs that you can’t realize (that’s not quite true: if you can come up with a great design, you may be able to get someone else to implement it). Part of my premise for this class (or at least this instantiation of it) is that we can all have different toolboxes – some students might be wizard programmers, some might be fabulous artists – but we all can have some common basic tools (e.g. sketching), and we can all explore designs using our respective toolboxes.

Now, if you’re saying “but I want visualization to be about writing fancy programs using complex data analysis methods and algorithms and spiffy programming things …” let me give you a bit of caution.

Building a custom visualization solution by programming should be a last resort. You should really believe that your problem cannot be solved by some easier method. Going back to the medical analogy, writing a program for a new design is like inventing a completely new (and therefore untested) treatment. Yes, if your patient has a mysterious disease and is going to die you want to take these drastic measures. Or, you might do an experiment if you believe that you can afford the risk on this patient in order to learn something to save the next ones (this is the excuse we use as researchers).

That said, all too often there are other factors that make us want to take the extreme measure. Sometimes, we just want to practice our inventive skills. Sometimes our “customers” think they want to have something novel (don’t make it look too easy!). Sometimes we really want to try out some implementation idea, or show off some challenging design idea. And sometimes, it might just be easier to re-implement a standard design than to figure out how to make an “easy” tool do what we want. (You’d be amazed how often I’ve found myself writing Python code for scatterplots because I wasn’t in the mood to wrestle with Excel). Sometimes, it’s hard to find a decent “easy” tool for something that should be easy (like graph layout).

Now What?

To give you a sense of where this goes into my class (not necessarily in this order) …

- We need to understand why we use visualization. Why can (well designed) pictures help people do things?

- We need to be prepared with critique and redesign techniques that we can use to explore the ideas by examining examples.

- We need to discuss abstraction so we can talk about tasks, data, and designs.

- We need to learn about encodings which are the building blocks that we use to make visualizations, so we can take designs apart and put them back together.

- We need to think about evaluation so we can assess whether or not we are making good visualizations.

- We need to learn about perception (how we see), since it helps us understand what is and isn’t easy to see. Color is an important part of this.

- We need to consider interaction because it is a useful tool in designs.

- We need to think about some core challenges like scalability.

- We need to consider some examples of challenging data types (such as graphs and volumes)