Using the metadata builder to guide an analysis

As we’ve been releasing new resources for interacting with the TCP files, one of the questions that keeps coming up is “This is great, but what are we supposed to do with this stuff?” In this blog post I’m going to show how you can use the Core 1660 Drama corpus (from our Early Modern Drama collection) and the Metadata Builder to look at plays which didn’t explicitly involve Shakespeare as an author. I also wanted to cover a range of genre classifications (by any measure of genre), and were a manage size.

Using the Metadata Builder, I have the option to collect a variety of metadata from the master spreadsheet associated with the Core Drama corpus. As I want to study the texts freely available as part of the TCP, I select the ‘Unrestricted’ option in Step 1 rather than ‘All’. In this particular case, I am interested in play companies, so I want to ensure I get metadata which will supplement and guide my analysis of play companies. Therefore, I select the following categories in Step 2: TCP, ESTC, Wiggins Number, Author 1, Authors 2-5, Title, Genre, Wiggins Genre, DEEP Genre, Harbage Genre, Wiggins Contemporary Genre, Date of Writing, Date of first performance, Play Company 1, Play Company 2, and Theatre [1]. I could have downloaded more metadata, but these categories seemed most suited to guide an analysis of one particular play company. Looking at the metadata spreadsheet and paying specific attention to the Play Company 1 category, I settled on the Admiral’s Men, as it is inclusive of a diverse range of authors (including Munday, Dekker, Marlowe, Chapman and Peele) while remaining a manageable size (21 plays).

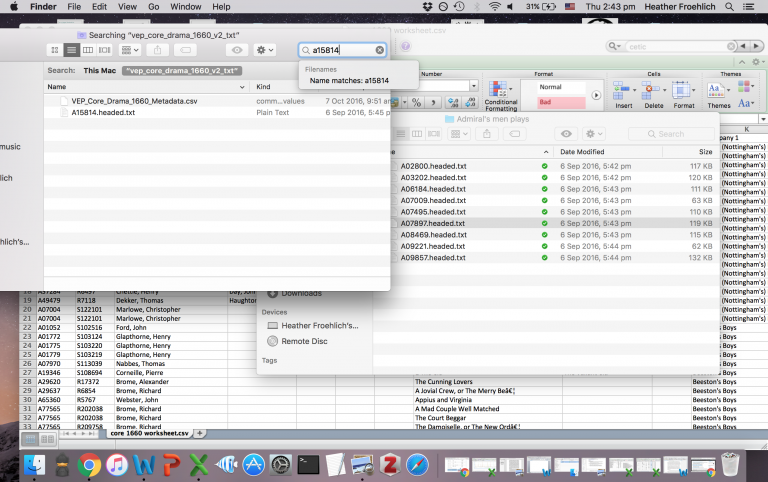

I then isolated the specific TCPIDs associated with each play-text belonging to the group I will now call ‘Admiral’s Men Plays’. Armed with this list, I copied these plays into a new folder to create a subcorpus of plays from the Core 1660 Drama Corpus. Here’s what that looked like:

Having made decisions about what texts to analyse and moved the files around to create a corpus of Admiral’s Men Plays, I now can set up a multivariate linguistic analysis using Ubiqu+ity to observe some specific linguistic features. I’ve previously written about creating your own rules for Ubiqu+ity, but this time I want to use the standard DocuScope dictionary, which is a rich classification schema of the English language. While I may not necessarily agree with every decision made in what makes up the DocuScope categorization of the English language, it applies the same rules to every text it is given to analyze, which means that it counts the same features every time. Using the default settings on the Ubiqu+ity site, the system sends me a zipped folder of results. Included in this zipped folder is a comma-separated values spreadsheet which reports how much of each file measuring what percentage of each category makes up the whole of the file.

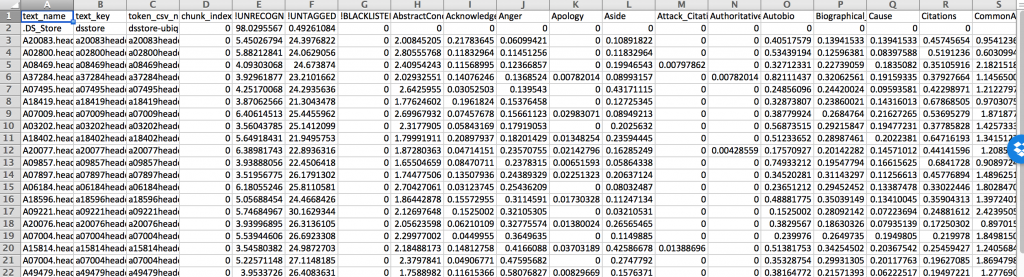

A selection of linguistic categories reported by the DocuScope dictionary

Due to the nature of how DocuScope categorises language, some linguistic groupings are more likely to be in use than others. For example, FirstPerson (I, me, etc) is more frequent than Apology (sorry, apologies, etc) due to the nature of how language is understood to be distributed: the small boring words like I and me are far more frequent than more contentful words like ‘sorry’ or ‘apologies’ (This is part of a phenomenon called Zipf’s Law and you can read more about it here). You may also have noticed that the filenames use the anonymized TCPID numbers; you can cross-reference for titles using the metadata spreadsheet.

Due to the nature of how DocuScope categorises language, some linguistic groupings are more likely to be in use than others. For example, FirstPerson (I, me, etc) is more frequent than Apology (sorry, apologies, etc) due to the nature of how language is understood to be distributed: the small boring words like I and me are far more frequent than more contentful words like ‘sorry’ or ‘apologies’ (This is part of a phenomenon called Zipf’s Law and you can read more about it here). You may also have noticed that the filenames use the anonymized TCPID numbers; you can cross-reference for titles using the metadata spreadsheet.

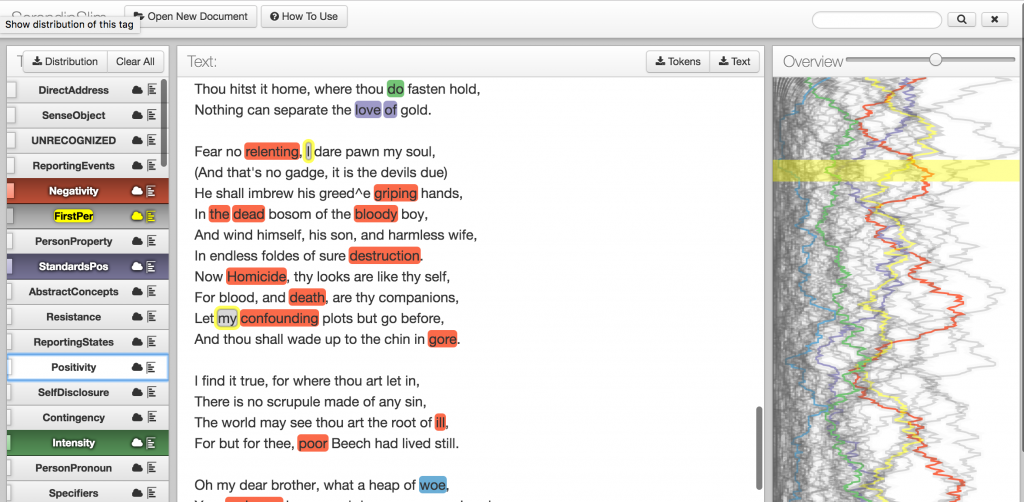

With this report, it is also possible to conduct a variety of quantitative analyses. Our colleagues have projected all of these categories into multidimensional space using Principle Component Analysis, but it is sometimes easier to focus on just a few features. By limiting the spreadsheet to only a handful of Language Action Types, the spreadsheet becomes far more manageable to work with. If I was interested in the category ‘Sad’, I could rank the spreadsheet using Excel’s sort function and see that Two Lamentable Tragedies has the highest quantity of ‘sad’ out of the subcorpus I have constructed. I can then see what other features are listed as highly-ranked for Two Lamentable Tragedies, or I can use I used the SlimTV TextViewer included in the downloaded Ubiqu+ity folder to identify other high-frequency linguistic categories for this play. With the SlimTV viewer, I can see that ‘negativity’ ‘intensity’, and ‘standards-positive’ are all highly ranked:

Negativity, Standards(Positive) and Intensity are all highly ranked in Two Lamentable Tragedies

And that’s just a jumping off point: what other plays share this linguistic profile? From here I could compare how these specific features are used in other plays performed by the Admiral’s Men. But that’s still broad of a research question, so here are some more specific ones to follow up on: Do others plays in this corpus you made also rank high in those features? How about compared to the majority of the plays in the Core Drama 1660 corpus? Do the prevalence of negativity and intensity correlate to the acting style or material this group chose to perform?

[1] The metadata we have comes from several sources, including the Database of Early English Playbooks (DEEP) and Wiggins catalogues. We have also performed cross-checking between these two resources as well as including further reference to the ESTC and JISC Historic Texts, where necessary.

(this information has been taken in part from the VEP Core 1660 readme file [pdf])

TCP – lists the associated unique TCP ID number for the play in question

ESTC – Short Title Catalogue records, in case I need/want to find out more information about these texts

Wiggins Number – in case I want/need to reference the Wiggins catalogue for a particular play; based on Wiggins catalogues published to date

Author 1 – Primary author

Authors 2-5 – any other assigned authors, where applicable

Title – the title by which the play is commonly known – often the contemporary title.

Alternative Title – any other names the play could be known as. For example, the play known as “Volpone” is listed as “Volpone” for primary title, and “Volpone, or The Fox” is considered the secondary title. (We also use the ‘secondary title’ category to describe printed titles when they are different to performed titles.)

Genre – these are the genres originally assigned earlier in the project by Jonathan Hope – either Tragedy [TR], Tragicomedy [TC], Comedy [CO], History [HI], Masque [MA], Interlude [IN], Entertainment [EN], Dialogue [DI], or Non-Dramatic [ND]

Wiggins Genre – based on information from the Wiggins Catalogues (published to date)

DEEP genre – based on information from the Database of Early English Playbooks [link]

Harbage genre – from Harbage’s Annals of English Drama (1989)

Wiggins Contemporary Genre – genre classifications based on contemporary (modern) understandings of genre, taken from the Wiggins catalogues (based on those published thus far)

Date of writing – all texts have been given a date of writing. DEEP doesn’t have a date of writing column but sometimes offers a date range under ‘date of first production’, so in these instances the earliest date was taken for date of writing – if Wiggins offers a fixed date for date of writing then this was taken.

Date of first performance – when the play is understood to be first performed, if known

Play company 1 – The company of first production according to DEEP

Play company 2 – DEEP’s company attribution (where applicable)

Theatre – theatre and/or location of production, where available